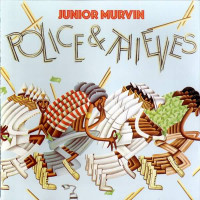

Hopelessness is a feeling that permeated the Jamaican populous in the late ‘70s. Crime was at an all time high, elections were both brutal and corrupt, and the common man was feeling the brunt of it all. (Maybe some of you can relate?) So, it was in this oppressive ether that roots reggae was born- a combination of holiness, righteousness, anger, and peacefulness that could project both rage and calm over a thick, lagging beat. Therefore, it really is no surprise that famed producer Lee “Scratch” Perry, who helped create the genre, released one of its masterworks… if not THE masterwork,

Vocalist Junior Murvin had been recording one off singles in Jamaica since the ‘60s and had a few minor hits. His angelic, cooing voice, tempered after Curtis Mayfield’s own deliver, was able to project a sort of common man perspective as well as a cosmic reflection. That being said, up until ’77, he had been recording mostly love songs on substandard equipment. Neither the lyrics nor the machinery was able to capture just what he was capable of.

And, if there’s one man that knows how to draw out an artist’s greatness, it’s the mighty Upsetter- see, for example, his other work with Max Romeo, the Congos, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Eric Donaldson, the Ethiopians, etc etc etc. So, it was really no surprise that the pair working in tandem, cut one of the finest records, ever- reggae or otherwise.

Opening with roaring horns of Jericho, the album signaled a defiant piousness. On “Roots Train “ Murvin called out in his gossamer, angelic voice “Roots train number one is coming!” The refrain signaled a positivity in the sign of negativity as well as an identification with the underdog. True, this general concept had been utilized before in reggae, but you’d be hard pressed to find it utilized with such rigorous righteousness.

No doubt, Perry himself lent the massive thunder to Murvin’s words. Recorded in the famed Black Ark studio, Perry provided his trademark SUPER HEAVY bass and drums, washed over with a blurry grain, all while hurling in floating guitar lines that didn’t so much play notes as bleed together into one acid-shifting line. Beynd that, Perry was a master arranger, hiding vocals behind vocals, sound effects just at the end of certain bars, and palcing Murvin’s voice front and center while the army of sounds behind him (mysteriously recorded on a four track record!) follow in a rumbling trail.

The pair also worked together to create some reggae’s most aggressive lyrics to date. “Police and Thieves,” which of course would be covered by the Clash, who also briefly worked with Perry, not only called out the badmen, but directly pointed fingers at governmental corruption. Calling out the cops (and by extension government officials) was one in the same as the robbers, Muvin and Perry were breaking taboos and also saying it like it was.

It would be one thing if Murvin went around simply pointing fingers, but throughout the released, he built his own bonafides through a, perhaps judgmental, devotion. On “Rescue Jah Children,” he struck out at the aforementioned oppressors in the name of youth. “False Teachin’” lashed out at modern capitalism through a series of biblical allusions. More to the perspective of the everyday man, on “Workin’ in the Cornfield,” he gazed out from his brutal day’s work at the wealth of a select few and ruminates on how a man even manages to survive in such an environment. As I said, the parallels are easy to see.

It’s tempting to say that Police & Thieves was influential on reggae, but that’s not really the case- punk is a different matter. Other acts, like the Abyssianians and Congos, would take the religious angle of Murvin to further extremes, but few ever managed to juggle the “Jah is great” aspect with Murvin’s everyday musings and harsh attack at modern culture. The other acts mentioned, seemingly, would prefer a more abstract, biblical allusion based approach, which while fairly mystical, lost the aggressive strike of Murvn.

Meanwhile, who could copy Perry? The fact is, no other producer had or has the vision and specific technical expertise… as well as the balls… of the madman, and therefore, more or less, no producer tried to combine sheer heavy dread vibe with otherworldly experimentalism that bafflingly worked so well in this context. That is to say, Perry often is given props for his experiments- but he’s not as often given credits for his fundamental skill and ability to work his experiments into something meaningful. He does all of that here in spades.

Despite their surroundings, both Murvin and Perry were able to find a sense of hope, and even whimsy, in the bleakest circumstances. That this record makes its 40th year this year could be a coincidence, but of we were able to ask Perry or the departed Murvin, they’d likely give a more ominous answer.