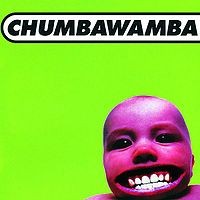

Chumbawamba

Tubthumper (1997)

Misanthropee

Anyone first encountering British anarcho-punk may find confusing Chumbawamba's veneration alongside bands like Crass and Flux of Pink Indians. It's true, though; mainstream pop's most infamous one-hit-wonders carry formidable punk cred. Their releases up to 1992's Shhh are often considered genre landmarks, and innumerable appearances on seminal anok compilations and at period activist events further attest to their former prolificness. They committed the ultimate sin, however, by signing to EMI for their 1997 full-length. Hardcore fans were unsurprisingly infuriated by this overt collaboration with a hated corporate conglomerate, and while the album sold millions worldwide, Chumbawamba lost many longtime supporters and were promptly forgotten by everyone else. Several core members eventually left, and the band now exists in a stripped-down acoustic incarnation.

Right now, though, disregard all that. In 1997, the band is at the peak of a long stylistic change--the logical conclusion of a career progression predating any hint of popular success. Nothing substantial here is new to Chumbawamba's output. Punk invective shines through pop simplicity and radio-friendly production as they attempt to marshal the best of both worlds, using finely polished hooks to disguise angry anarchist mantras as dancehall chants and dopey alt-rock refrains. Business as usual, in other words, but more consistently composed and with greater production values. Pictures of Starving Children is seminal, but this is Chumbawamba's defining release, and they apparently intended it as such at the time--despite later statements to the contrary.

The musical style overall is still cut-and-paste syncretic, but Tubthumper is more aggressive and modern rock-oriented than their previous outing, Anarchy. This is a pop record from beginning to end, and Chumbawamba keeps the energy high by avoiding somber acoustic ballads like "Homophobia." There's no folk or song length a cappella here, this time only hinted at by an abundance of rich vocal harmonies and rootsy flourishes--and maybe for the best. The band's most interesting work has always been its loudest and most exuberant.

It's impossible to further discuss Tubthumper's content, though, without first addressing notorious popular hit "Tubthumping," which bafflingly opens the album and is guaranteed to give any first-time listener a false impression of the band's music. In a shining example of Chumbawamba's worst songwriting habit, "Tubthumping" repeats its banal chorus couplet more than enough times to drive any listener insane with rage (at least 24, by my count). No other track in their catalog better exemplifies this infuriating tendency to extend one minute's worth of music into five of repetitive pablum. I guess it's meant as both a celebration of working-class resilience and a rebuke of the apathy engendered by boozing one's problems away, or something; but the American booklet is missing explanatory liner notes, so us Yanks are left assuming it's a yobbish pub anthem.

Fortunately, unlike every other record you've ever heard, it's all uphill after the first song. "Amnesia" turns things around with a thumping four-on-the-floor beat and metallic guitars, like a female-fronted pop mutation of early Nine Inch Nails. Strong hooks and sardonic lyrics assailing representative democracy make it the most memorable track here, and it sets the tone for what follows far more appropriately than the actual opener. Fun fact: It was a major hit in Britain but didn't even register Stateside. In "The Good Ship Lifestyle," another highlight, a sparse breakbeat-driven verse dives into a thundering deathpunk chorus. Breezily paced "Drip, Drip, Drip" masquerades as an average alt-rock single, but it demands attention with assertive drum loops and trumpet riffs recalling mainstream two-tone. Industrial-tinged "Mary, Mary," meanwhile, is almost heavy enough at times to pass for a Ministry song. There's ostensibly a lot of stylistic variety among tracks, and the production sounds great. But as a whole, the soft verse/loud chorus/ad nauseam formula and derivative dance rhythms on every goddamned song can make for an unpleasant listen. This is especially true if you appreciate the genres being diluted here. Excluding the samples bookending every track, the music on Tubthumper barely amounts to 40 minutes, but it tends to drag on like 400.

If it weren't for the lyrics, delivered by no less than five highly capable vocalists, Tubthumper would deserve its place in the dustbin of 1990s radio-ready alternative. When you're in the business of making music for agit-prop's sake, though, instrumentation is just a slick vehicle for invective. As such, Chumbawamba mostly delivers on the lyrical front with their trademark celebratory and sarcastic anti-authoritarian screeds. Most of the subject matter is cleverly tackled, with typical concerns of British anarchists and fellow travelers addressed in a novel-enough way to make the ideas accessible to outsiders. Ebullient rocker "The Big Issue" is a prescient and weirdly cheerful ode to the modern cycle of indebted ownership, foreclosure and homelessness, directing those stranded on the street to enact a different kind of repossession: "But there's a house / That I know / Safe and warm / And no one ever goes there." Attacking Western xenophobia, "Scapegoat" laments that while "This island is big enough / For every castaway," people often project blame for their own hardships onto innocent cultural outsiders. Over a decade later, with irrational anti-immigration sentiment in the U.S. and E.U. still fierce, it's just as relevant.

Like its instrumentation, though, in places the album suffers lyrically from maddening repetitiveness and oversimplification. "Outsider" was seemingly intended as an inspirational dance floor paean to free thought, but five short lyric lines stretched over nearly four minutes of insufferable glowstick-worthy trance lose all potential impact by the end. That's probably part of the point, as certain subjects that may seem inscrutably British to international listeners benefit from this dumbing down. It's hard to miss the point of class-warrior "I Want More," whose chorus declares that "This is tearoom England / They'll kick your face in so politely." But of course, it's all attached to more endless, vapid chanting à la "Tubthumping," and boredom soon smothers any potential appreciation of the meaning behind it all.

In the end, one must judge Tubthumper not just on its musical merits, but also on its success in justifying those arguments Chumbawamba clung to at the time in defense of "going major." Did they reach a bigger, broader audience? Of course. But did they succeed in spreading "The Message"? Not in the slightest. Having intended to use popular music as a Trojan horse for radical politics, the last of British punk's capital-A old guard is instead doomed forever to an association with the Macarena in the public consciousness.

In aforementioned "The Good Ship Lifestyle," Chumbawamba cautions against solipsism, depicting a lone sea captain defiantly--and purposelessly--sailing onward long after his crew has abandoned him. A critique of so-called lifestyle anarchism, it's also an obvious rejoinder to the blind anger rightly expected from lefter-than-thou critics following the EMI signing. There's a valid point here; conviction that only one's own viewpoint is ideologically sound approaches nihilism. But more than a decade after the album's release, the song in retrospect takes on an unintentionally ironic tone. EMI may have long divested itself of arms manufacturing, and previous label One Little Indian may have been no less capitalistic in the first place. But the symbolic gesture of collaborating with "the enemy" saw Chumbawamba impulsively strike out on their own, away from longtime socio-political moorings and into known shark-infested waters. And we all now know how the voyage ended.

"So steer a course / A course for nowhere / And drop the anchor / My little empire."