Crass didn't define punk as much as show punk had no set definition. Through a string of six albums and many, many singles, the band used boot boy rocking, expressionist soundscapes, and straight up screaming to not only express a point, but to engage in direct action.

Now, twenty-six years later, Crass have finished re-releasing their six studio LPs, entitled The Crassical Collection. The reissues did not come easy. Just as founding member Penny Rimbaud was planning to improve the sound of the original releases and update the art of the albums, a few members of Crass became strongly opposed to Rimbaud's plan.

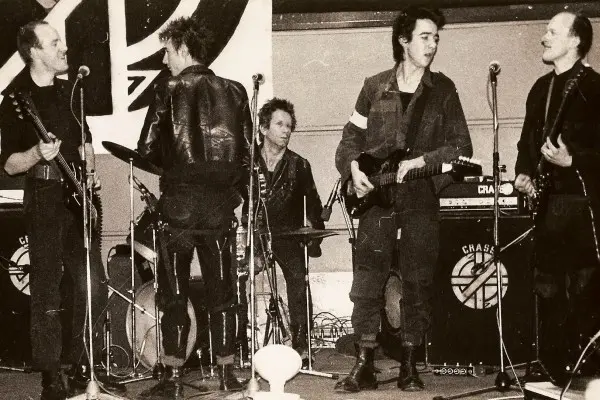

Punknews features editor John Gentile recently spoke to founding members Steve Ignorant and Rimbaud about what Crass was, what Crass is, and what the reissues mean.

Reality Asylum

What most people don't know is that Crass, the band that incited a police investigation because they had a record that included the lyrics "I vomit for you, Jesu", the band that dedicated an entire album to feminist issues at the height of the boot boy era, the band that faked a recorded conversation between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher and sent it to national news publications, the band that won a landmark appeal after being convicted of obscenity, the band that revolutionized the concept of what punk was and could be, started out in a hospital.

Founding member and vocalist Steve Ignorant explains that Crass found its genesis in his desire to meet girls. "I was working at a hospital and this girl comes in with baggy trousers and plastic jewelry. I said, 'What's this all about?' She said 'It's punk rock,' and then she said 'There's a band playing tomorrow.' I asked 'Are you going to be there?' She said 'yeah,' so I said 'alright.' So I went down there and walked into the place. My jaw just dropped. The Clash were playing, and there's [Clash bassist] Paul Simonon, about six foot two, looking cool. The girl didn't show but at the end of it when the Clash finished, people were going on about 'You're shit!' [Clash vocalist] Joe Strummer comes back and says, 'If you think you can do any better, go ahead and start your own band!' That was it for me."

Taking Strummer up on the challenge, Ignorant made his way to a five-hundred year-old cottage in Essex called Dial House. Although over its lifespan the property holding Dial House had served as a hunting ground for Renaissance-era nobles, a retreat for Victorian agriculturist Primrose McConnell and a farm, by the time Ignorant arrived, Dial House was being used as an anarchic-pacifist open house. One of the most constant inhabitants of the property was a former hippie who loved jazz, liked to garden, and often walked around naked. He called himself Penny Rimbaud, taking the last name from famed poet Arthur Rimbaud and the first from the price it cost to use a public toilet in London.

Ignorant knew of Rimbaud through his older brother who had briefly stayed at Dial House. Knowing that Rimbaud had a drum kit, Ignorant told the older hippie that he wanted to start a band. "Alright," replied Rimbaud, "I'll drum for you." Thus, Crass, named after a line from Bowie's Ziggy Stardust, came into existence as two guys making a racket in a cottage; one shouting lyrics adapted from a poem about killing chickens, and the other sitting behind a moldy drum kit pounding out rat-a-tat-a-tat-a-tat TAT!

White Punks on Hope

All at once, Crass formed the image of punk and shattered it on the same track. Crass' debut, 1978's The Feeding of the 5000 opens with the track "Asylum." On it, a metallic, amorphous stream of feedback roars across the speaker as vocalist Eve Libertine, reading Rimbaudâs lyrics, sneers, 'I am no feeble Christ, not me / He hangs in glib delight upon his cross.' Soon after she hisses, 'He is the ultimate pornography! He he!' It gets more graphic from there. The track was so shocking to the population at the time that the original pressing plant refused to include it on the album's initial run. Once the track actually was issued on a later pressing of the album, the police visited the band at Dial House in order to give them a warning to "watch their back."

But then, just as it seems like 5000 would be an experimental, acid-trip of a record, it snaps into the classic "Do They Owe Us a Living?" which has a riff and a refrain as snappy and as invigorating as any other rock-n-roller you could name.

Ignorant talks about how the components of Crass caused it to be such an undefinable entity. "Penny's background came from '60s jazz, classical, the Beatles, stuff like that. My musical background was ska, blue beat, a bit of The Who, David Bowie. I was obviously tying to pull for a more Clash-y, Sex Pistol-y type thing, while Pen was pushing for a more avant garde jazz type thing. I was trying to be David Bowie but came back as Steve Ignorant. I think that's where we were so opposite, our backgrounds. Then when you put into the equation, Pete Wright, his background came from Frank Zappa. So you had this real mish-mash that we were all trying to put into that stuff."

Independently unaware of Ignorant's comments, Rimbaud somewhat humorously comments on the band's sonic make-up: "My background is much more through jazz and experimental music. Certainly, when we were preparing songs, I wouldn't be interested in what the Sex Pistols were up to. I'd be interested as to what Aaron Copeland was up to. I can't actually compose. I can't write 'songs.' I find the rhythmic properties of rock and roll tedious. I've always found it to be unbearably simpleâthe whole album in a four-four beat. Which is to say, I don't not like all rock and roll. I like David Bowie and find him extraordinary."

Ignorant comments that perhaps it was this conflict, and difference of objective, that made Crass so unique. "We were two blokes from a different background that just got on. On one hand, Pen was able to push me to do these outrageous things. On the other hand, it'd be me saying, 'Nah, Pen, it's crap.'"

From 5000 Crass expanded out in all directions, not so much defining punk as showing that punk had no solid definition. On Stations of the Crass they increased their attacks against religion and the government, as well as taking aim at the cliché that punk was becoming. During the recording of the feminist-themed Penis Envy, the band slipped copies of a track credited to "Creative Recording And Sound Services" into teenage girls' romance magazines. Shortly thereafter, Crass was tried for releasing obscenity; after losing in the trial court, they appealed and reversed nearly the entirety of the verdict, thereby setting new precedent as to what counted as "obscene" in the United Kingdom.

In 1982, Crass created a vocal mash-up of President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher which made it appear as though the pair were in cahoots, and planning to make Europe a battleground against Soviet Russia. The tape was anonymously disseminated to news outlets which, for a brief time, were entirely fooled by the hoax.

Their final record, Ten Notes on a Summer's Day was nearly devoid of guitar, arguing to punks that punk rock wasn't five guys in a band. Rather, punk rock was revolution itselfâsonically, socially and politically.

In Which Crass Voluntarily Blow Their Own…

In mid-2010, some twenty-six years after the band's official dissolution, the members of Crass found themselves sitting around a table⦠a negotiation table. Tempers were flaring and the band had split into two camps; those that wanted to re-issue Crass' six seminal albums with updated art and sound, and those that did not. Rimbaud, Ignorant and Crass' art director Gee Vaucher wanted to re-release the Crass discography as remastered by Rimbaud, while in the opposite camp, bassist Pete Wright, vocalist Joy De Vivre and guitarist Phil Free opposed Rimbaud's remasters.

Although Crass' albums had never went out of print, the CD versions (and even the vinyl versions) were plagued by poor mastering and digitizing, giving them a tinny sound that compressed the range of sound from a massive soundscape to mono-sonic screech.

Prior to the whole conflict, Rimbaud remastered the final Crass LP Ten Notes on a Summers Day - The Swan Song on a whim, an album which was principally constructed and recorded by Rimbaud when it was originally being made from 1984 through 1986. Pleased with the results, he asked Ignorant if he should try to remaster the whole discography. Ignorant gave Rimbaud the okay, and over the next four years, Rimbaud worked at updating the Crass catalogue.

Judged on an artistic level, The Crassical Collection is a pretty top notch reissue of Crass' studio albums. In the early nineties, the joke formed that "Crass read better than they sounded" due to the limited range of the technology that was used to compress recordings to CD format. The new remasters, which do not remix the sound, render that point moot.

Not only are the sounds on the remasters crisper, but the delicate interplay between the hordes of sounds going on at any one time in a Crass record is evident. Where Crass used to be noise for the sake of noise, it is now abrasion for the sake of artistic investigation. Plus, as much as many punks hate to admit, Crass rocked. When they played or imitated rock music, Crass' licks, combined with Rimbaud's pitta-pat-pitta-pat drum, combined with Ignorant's barking, got the listener as out of his/her skull as even the most reverent rock music.

Of course, the avant garde side of Crass is amplified as well, from the parts where there is no drum cadence but just Eve Libertine shouting lyrics like "These heroes have run before me / now dead upon the flesh piles, see?" amidst a backdrop of what sounds like machines ripping themselves apart, to the side where Rimbaud relies heavily on cold, robotic synthesizers, creating a feeling of absolute dread, to the side where the band recorded a 45 minute song in one live take. The full range and interplay of unusual sounds, which were muted previously, are brighter, stronger and connect more directly than they ever have in the past.

Rimbaud explains his reason for wanting to improve upon the sound of the original masters. "I think you can parallel it to a Velázquez in a museum, which you can't see anymore because the varnish has turned it almost black. You know, in many cases, they've gone back to the master paintings and cleaned them, and suddenly you can see the bright colors. Suddenly, you can see the paintings as they've painted them, rather than as time has recreated them."

Rimbaud goes on to comment that even in transferring music from the studio to tape and to transfer it to a record or CD is changing the work. "The recording itself is a reproduction. The first stage is the tape, and then it is transferred to the product. Well, in all those stages it loses things. The fact that we were limited to the technology of the day in making it sound that way is the fate that it will carry through history. For the detractors who say 'it ought to be left as it was,' I think that it should be left sounding as it did sound, not how it was left sounding due to the limitations of the era, so that's my riposte to that!"

Regardless of which side you're on, Rimbaud is right in that the new masters do sound much, much better than the original releases, making Crass sound much more live and much more tactical. Ignorant comments on the interplay that is prevalent on the re-issues. "I think the reason that Crass' music was as unique as it was, was because none of us were proper musicians. None of us could read music."

Rimbaud also comments on how the remasters improve the quality of the sound. "My concern was to make [the] songs as sound as good as they possibly could. One of the things that we always had problems with was pulling out the guitar sounds. Finally, you can hear the guitar sounds for the first time ever. Well, for the first time since we were in the studio recording."

He further states that despite producing the remasters, he wasnât tempted to edit or show preference for his contribution. "We acted as a band. I believe that Gee, who did the artwork, and I who did the remastering completely honored and respected the fact that we were a band. I mean, for example, I certainly didn't try to make my songs sound better than Pete's songs. I certainly didn't try to bring the drums up because I was the drummer. That's not production, that's self-interest, and I'm not concerned with self-interest. When I was working on the remasters, I was working in the same place as when we were working together originally, a place that I believed was a place of caring, a place of trust, a place of love. And that's what I think of the studio and always will. Personal involvement doesn't come into the issue."

As to the sound, Ignorant talks specifically about "Mother Earth" from Stations of the Crass, a track that might benefit the most from improved sound quality. "If you take 'Mother Earth', which is about Myra Hindley who committed awful crimes in the '60sâwe were at the rehearsal room and Penny Rimbaud was saying to Phil Free, 'Make your guitar sound like it was stabbing someone.' We tried to work on sounds, so instead of having music behind the lyrics, it was more of an atmosphere, almost like a film score."

Likewise, because the sound benefited so much from remastering, Rimbaud and Gee Vaucher chose to create new artwork for the CD versionsâthough perhaps as a way to respect the past, the CD versions also include all of the original art and the new vinyl versions retain their original art. Rimbaud feels that the art needed updating because in the wake of Crass, imitators had robbed the band of its unique design. "I would go into a retail store and see our stuff. It looked tired and was sort of thrown in with all the old punk records and it had lost its vibrancy," he says. "When we were around originally, the covers were unique. No one else was doing black and white. No one was doing letters like we were. At the time that was very original and very exciting to people." Crass had such an impact that soon its imagery was being used by nearly every other punk band. Rimbaud continues, "Fifteen years down the line we've been flooded with imitators. You have innovators and imitators. The imitators make art become product. All the others now have a couple of dead bodies and bad print. I am interested to say 'This is how it did look.' If they don't want the new packaging, they can just resort to the old packing. So, I feel comfortable about that. The people complaining are the same people that are stuck in the same things they were thirty years ago."

Once Rimbaud had an idea of how he wanted to update the Crass catalogue, he presented it to the other members of the band. That's where things went south.

Major General Despair

Upon seeing Rimbaud's proposals for updating the catalogue, and the work that Rimbaud had already completed, Pete Wright expressed dismay. In a February 2009 email to Southern Records, the label working with Crass and Crass Records in reissuing the material, Wright stated that, although he also wanted the catalogue to be re-released, he was dismayed that Rimbaud had remastered some of the catalogue without first contacting the entire membership of Crass. Later that day, Wright emailed Joy De Vivre and Phil Free expressing that the failure to get in touch with everybody to talk it over before anything was done, was a serious failure and that hiring a typesetter friend of Gee's was premature, among other things.

Missives went back and forth between the members of Crass and Southern Records for over a year, with the communications growing more detailed, intricate and complicated with each dispatch, as the band tried to reach an accord. Tensions became increasingly strained and finally, in the summer of 2010, the band agreed to meet to see if they could come to an agreement as to how the reissues could be handled. That meeting was the last time Crass as a whole contemplated reissuing the discography.

Ignorant explains what happened at the meeting. "Basically, what it came down to was bunk! For me, it came to a stalemate. You want the reissues to be good so you can see the artwork, read the lyrics. I don't think it made them worse! I think it made them better, you can actually hear it. I was like, 'Why can't we compromise?' One or two others, say, they didn't like the color. Well, let's change it then. If you don't like the studio work, we can go in the studio again. But, it really wasn't any of that. It was more personal, rather than artistic."

Rimbaud agrees that the band developed into two factions not over any arguments with the art, but over personal differences outside of the band. Rimbaud says, "It was sort of a pretty unhealthy result. I haven't been forgiven by the other camp for having done so. I'd like to point out that the criticism hasn't been of the quality of my work. No one has ever questioned my art before and no one can question that now. With the critical acclaim that the reissues have received, you can hardly accuse me of undermining the Crass story or anything."

"The argument between myself, Pete and his supporters was more to with the sort of social and political life that we spent together here at Dial House," Rimbaud continues. "There were unresolved questions and unresolved issues. I have absolutely no respect for people that try to resolve those issues by picking up on something that has absolutely nothing to do with the true issues. So in a sense, I didn't take Pete's criticisms or attacks seriously. I knew where they were coming from, and they were not coming from where he said they were coming from. He was using The Crassical Collection as a sort of platform to attack certain social and political issues that are unresolved between a couple of us. I quite wish that Pete had confronted me personally so that we could have resolved those issues, but there is no way that I can talk to him because he won't allow it."

Ignorant explains the conclusion of the meeting, which indirectly led to the production of The Crassical Collection. "At the meeting, Penny got so upset that he left early. He called me later in the night and said, 'What are we gonna do?' I said, 'Fuck it! Let's release it and if anyone complains, or gets a court case going, I'll take full responsibility."

In a sort of poetic motif, just as Ignorant started the band, he pressed the button to start the production of the reissues. Although Wright initially threatened to file a lawsuit, he eventually sent a letter to Joy De Vivre and Phil Free stating that he would not. Ignorant comments on the threat of a lawsuit, "Well, I haven't been sued yet. Ha!"

End Result

Regardless if Rimbaud was presumptuous in remastering the Crass catalogue before meeting with each member of Crass, or if Wright is actually expressing unrelated grievances in the form of The Crassical Collection objections, it is hard to argue with the end result. The Crassical Collection sounds phenomenal. The packaging is beautiful. The essays are informative. Really, the legacy and message of Crass is presented in its best, most multi-textured form to date, and the band's legacy is done justice.

On the debut album The Feeding of the 5000, they are a tight unit ripping out simple, yet potent song after simple, yet potent song. On Christ - The Album, they create a monolithic assault on the government, and form what might be the first punk concept album. On Ten Notes, they abandon guitar completely and cut an amorphous side-long song that is as much dream pop as it is Lovecraftian horror.

As Crass grew and expanded, it evolved from being the band that Ignorant started to a collective of seven or eight members, each of whom had their own input into the band. As the band matured, Ignorant's studio prominence declined somewhat in lieu of having more voices on the recordings. In fact, on Penis Envyâan album dedicated to feminist issuesâIgnorant was entirely absent so the band could feature women vocalists exclusively. Near the end, both Yes Sir, I Will and Ten Notes were largely Rimbaud compositions, lyrics and productions.

Does Ignorant feel that Crass was taken from him, or does he feel that Crass should have evolved into the amoeba which it eventually became? "I'd agree to both of those. I did feel that the music was taken out of my hands. That is the way it went. The way it ended up as this amoeba actually worked. The first album we put out was me being a boot boy, shouting and screaming and all that. On Penis Envy, it's all women on the subject of feminism and kudos to them for that. I thought that was fantastic. It so unique and no one else had done it."

He continues as to how he managed to fit into the band as they grew: "On Christ - The Album, I found it difficult to fit in there. So, I was prepared to be the mouthpiece and I trusted what we were saying as a collective. I didn't think that my input got washed away, because I've always been the one hanging around the bar, rubbing shoulders with people, hanging around and just being there. I don't think anyone else could do the vocals like I did."

Although both Ignorant and Rimbaud seem proud of Crass, Rimbaud in particular seems somewhat frustrated that within the punk community, he is known as "Penny Rimbaud of Crass," with most fans ignorant of the vast body of work he created both before and after Crass existed. He says, "I'm rightly proud of what I did with Crass. I'm overjoyed with the long term effect that it has had, and how it has affected people's lives, whether it's through protest movements, or how people grow their own food. I'm proud of how it existed outside of the rock and roll framework. In a way that stems directly from us, not entirely, but in part." But he also comments on the downside. "As an artist, Crass is like carrying a lead weight around your neck. It has been hard for me in that regard. I've scared off what I call the dinosaurs of punk. Initially, when I went back on the road, I was getting punks who were only interested in Crass. But now I'm freer. The audience that I now have are adult, and intelligent enough to make their own decisions, and are not going to imitate."

Interestingly though, Crass face the same issue that they faced when they originally put out the second press of The Feeding of the 5000. According to the booklet of 5000, once the initial run of that record had depleted, the band decided to press the record on their own so as to not subject any small labels to the threat of obscenity laws. On the decision to do so, Phil Free asked Rimbaud, "Doesn't that make us capitalists?" In the booklet to 5000 Rimbaud doesn't answer Free directly, but now does state that his opinion on selling records has always been the same. He says, "The fact is, if you want people to hear what you are doing, if you want to have an effect, we took the right course. There wasn't any other member of the band that could set up a label, so in that respect, you had to be a capitalist. I'd point out that they were happy to accept the royalties, but they didn't want to be capitalists. For me, there was no conflict at all. If I can get like forty thousand then that forty thousand will go into a new project. I'm not afraid of it. That's the common currency. One has to accept that we live in a capitalistic society, I don't like it. I don't think money is intrinsically wrong, it's how it is used. If I got forty thousand for a record and went out and bought arms for some cruel war, than I would not be using that money well. If that money is spent on a youth center, rape crisis center, or for underprivileged people or to publish a work, that's a good use."

Ignorant seems to agree that Crass' activities and releases were put to good use. He says about Crass meeting its objective, "I got a little bit of laughs, a couple of girls, a little bit of money, a little bit of adulation, but I didn't make a fortune, didn't get famous. That's pretty good. On the political scale, we could have done more. We didn't stop war. We didn't stop capitalism. But I'd like to think that we were a little part of the opposition movement and really were a part of something."

When looking back on what Crass achieved, Crass' effects, and Crass' legacy, Rimbaud seems as proud as Ignorant, but even more firm. He says, "I've had conflict with some members, but I never had any internal conflict. I never had any doubt. We had the effect that we had because we were able to produce art. If we were never able to produce art, then we wouldn't have had that effect. I'm glad that we had that effect because the world is a better placeâI don't know by what scale or degree, but I believe the world is a better place for things that we did thirty years ago."