When the Marked Men announced in 2009 that their fourth full-length, Ghosts, would be their last before taking an indefinite hiatus (or whatever they were calling it), the depth of the apparition message went largely unrevered. No, the Marked Men weren't "dead." But, with each member's various commitments â including the expatriation of guitarist/vocalist Jeff Burke to Japan â effectively preventing the group from doing those things that ostensibly qualify what it is to be a band (writing, recording, touring), they decided to pull the plug. Reflecting on their potential dissolution during the final days of mixing Ghosts, the band said: "It was sad and strange⦠to realize that there would be no more Marked Men." Despite their quasi death, the spirit (and influence) of the Marked Men very much carried on through side projects (Mind Spiders) and unrelated bands (Bad Sports) alike, providing ample material for the rejuvenated garage rock scene. As it were, the unrealized portension of Ghosts is not some lingering pop-punk poltergeist phenomena (fuzzy, lo-fi recordings; urgent melodies); rather, a literal ghost: undead, unrested, and foaming with conviction. They meant Radioactivity.

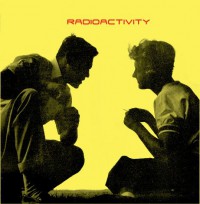

While Burke was in Japan, he formed the Novice, releasing their lone self-titled 7-inch via Dirtnap in May 2013. After returning to Texas, Burke continued the Novice under a new moniker â Radioactivity â with Marked Men bandmate Mark Ryan and Denton staple Gregory Rutherford (Mind Spiders, Bad Sports, High Tension Wires). Contributing both reworked Novice tracks and original material, the end result is the eponymous Radioactivity â 13 songs built on '60s garage rock aesthetics, '70s power pop themes, and an unrelenting bent toward infection. Radioactivity sounds like the Marked Men because it is the Marked Men â back from the dead, an evanescent manifestation offering a mix of relief and closure for those still reeling from the Men's absence.

Burke and company demonstrate they can play garage rock that is both sedative and immediate, belting out songs like "World of Pleasure," where jangly guitars spit out 5-chord pop punk and vocals are produced at such low fidelity you'd be convinced it was recorded using analog equipment from the '50s. Juxtaposing his falsetto chorus with a calmer, lower register in the verse, Burke amplifies the intensity of the former while evoking the anxiety associated with loss â of control, happiness, etc. "Locked In My Head" employs a similar intelligent melody, using two guitars playing identical progressions on different frets to create a robust, uncomplicated sound before reuniting for the deceptively pleasing chorus.

Radioactivity don't need to rely on instrumental gimmicks or vocal tricks to keep attention. Instead, they write songs with traversing chord structures, creating unique, engaging melodies that stand on their own, and adding depth and character by sticking to the basics. On "Sickness" a fuzzed-out guitar leads the charge, keeping rhythm as the second guitar solos out of the verse and through the first half, buoying the energy and maintaining a sense of urgency. At other times they're more traditional, using extra guitar work (simple, fast solos) to careen songs through a bridge ("Don't Try", "Falling Out"). But above all, the songs don't wear out their welcome â they vary in structure and are effectually terse. For example, "Locked In My Head" follows an ABABC scheme, succinctly eliciting a sense of frustration while using its brevity to magnify the feeling vis-Ã -vis the repetitive outro, which is accentuated by Burke's strained vocals. There is nothing exceptionally complex or challenging in how Radioactivity construct songs, but their progressions always manage to capture an emotion holistically while using textbox devices to emphasize affection.

This is an important quality to have, especially for a band who soak their lo-fi vocals in so much reverb it is often difficult to understand what exactly they're singing. While most of the lyrics are comprehensible enough to discern the subject matter, Radioactivity give new meaning to the notion of "lyrical interpretation," since their enigma doesn't stem from intention, but pronunciation. The affect creates a hyper-individualistic experience â the listener is charged with deciphering and attributing meaning based, in some part, on what they think is said, not what is actually said. The message ends up working on a very personal level. Still, the topics, while unapologizingly trite for pop punk, remain fresh due to their accessibility and relatability. Often relying on an amorphous, ubiquitous second person, Burke ruminates on emotions pervasive to the human experience, such as betrayal, depression, mental control and vulnerability. Not to mention, he's often quite clever: "When I get too close, you say you can't see me" ("Don't Try").

The reality is Radioactivity picks up right where the Marked Men left off, offering a particularly idiosyncratic strain of nascent garage rock. And, let's be honest: that isn't an entirely bad thing. We all wanted another Marked Men record, anyway.