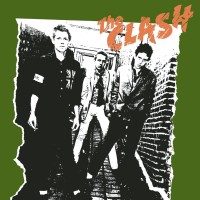

While the Clash’s self-titled debut album was released in 1977 in the United Kingdom, it was released almost a full two years later in the United States to promote their first US tour, making it their second US release rather than their first in this country, as Give ‘Em Enough Rope had some out in the US in 1978. [1] Even though The Clash had been the best selling import of the year when it was released, CBS was still worried that the album was not radio friendly enough for the United States.[2] What modern listeners might have trouble understanding, though, is that the Clash had a lot of non-album material to pull from. At the time, it was much more common than it is now to release stand-alone singles that never appeared on a full album. As full albums became more popular, this practice fell out of favor, although the rise of digital downloads is facilitating a slight revival of the stand-alone single. The Clash released a slew of stand-alone singles over the year, including some of their most popular songs such as “Bankrobber†and “This is Radio Clash,†but their most prolific period of releasing stand-alone singles was between 1977 and 1979.[3] So when CBS chose to pull some of the songs that it didn’t think would go over as well with American audiences, they filled in the gaps with four stand-alone singles, one B-side, and one song from a 1979 four-song EP called The Cost of Living. The result is that the US version of The Clash served as a sort of greatest hits compilation of the Clash’s first three years as a band before they made the massive shift from a more traditional punk sound to the more eclectic sound of London Calling and beyond.

When I was a teenager (which was in the late-90’s and early 2000’s) the US version was still the version I ever saw in stores stores, where as today both versions are readily available, and most digital music sources seem to default to the original UK version, so it’s easier to compare the two now than it’s ever been. The tracks that were removed from the original version were “Deny,†“Cheat,†“Protex Blue,†“48 Hours,†and the original version of “White Riot.†Substituted in their place were “Clash City Rockers,†“Complete Control,†“(White Man) in Hammersmith Palais,†“I Fought the Law,†“Jail Guitar Doors,†and a re-recorded version of “White Riot.†While I’m at a loss to see any significant difference between the two versions of “White Riot,†I’ve always believed that the songs they replaced were stronger than the ones that they left off, with the notable exception of “Cheat,†a song so good and widely known that Rancid managed to cover it in the 1990’s when it wasn’t easily available in the US. However, what has always baffled me, and continues to baffle me to this day, is why, when deciding which tracks to be left off of the US release, CBS did not decide to remove the song “I’m So Bored with the USA,†which seems like the most obvious track for the chopping block, even if the only thing you know about the song is its title.

In the movie High Fidelity, there’s a scene where the main character puts “Janie Jones†on his list of “Top Five Side One, Track Ones†of all time. However, while “Janie Jones†remains on the US version, CBS also decided to rearrange the track order of the album significantly for the US release, putting “Janie Jones†as the first track of side two. Instead, the US version’s first track is “Clash City Rockers,†which I personally think is a much stronger album opener than “Janie Jones. “ With its infectiously chunky guitar riff (which they would later copy almost exactly for “Guns on the Roofâ€), “Clash City Rockers†makes for a much more dramatic opening to the album. Lyrically, the song lays out a manifesto for the punk movement that, while echoing the sentiments of other early punk artists, is specifically from The Clash’s point of view. Most notably the song declares punk to be the new king of the music industry, while taking shots at the popular glam artists of the time that they sought to replace, like David Bowie and Gary Glitter, but aligning themselves more reggae artists like Prince Far I. Essentially, “Clash City Rockers†is a 1970’s punk rock dis track.

The Clash loved to do cover songs, but many of the songs that they covered, like “Police on My Back†and “Police and Thieves, are now mistaken as Clash originals since the originals never really stood the test of time the way the Clash did. Of all their covers, “I Fought the Law†is probably the most high profile song the Clash ever covered, as it was originally written and recorded by The Crickets in 1960 for their first album after Buddy Holly’s death, then became more popular five years later when it was re-recorded by The Bobby Fuller Four. Despite this, “I Fought the Law†is still mistaken as a Clash original from time to time, and even if they didn’t write it, they made it a punk standard, and influenced many punk artists over the years to cover the song both on their albums and as an impromptu live cover. Even the 2004 Green Day cover of the song (a digitally released stand-alone single) sounds like a carbon copy of The Clash’s version. It was a pretty perfect song for The Clash as punk was considered to be an attempt to reset music back to the early rock and roll era, but with more of an outlaw attitude. The Clash were particular fans of Buddy Holly, and on one American tour they famously took a trip to Buddy Holly’s grave in Texas at midnight to light candles and sing songs[4]. Their version of the song took the jangly pop tune and cranked up the velocity with a furious drumbeat from Topper Headon, who joined the band between the recording of the UK version of The Clash and the recording of â€I Fought the Law.†It’s widely believed that Headon would have gone down in history as one of the greatest drummers of all time if it weren’t for his heroin addiction, and the difference in talent level between Headon and the Clash’s early drummer, Terry Chimes, who appears on most of the tracks of this album, is very noticeable.

I could literally write pages on “(White Man) in Hammersmith Palais,†as it is literally my favorite song ever, but I will try to keep it brief. The song starts off as a critique of an all night reggae show at Hammersmith Palais that Joe Strummer attended with his friend Roadent.[5] He critiques the performance for not being “roots†enough, and smoothing out the rebellion of reggae into more of a pop-reggae sound. Most people say that the song then moves onto other topics, but I’ve always seen the lyrics as somewhat connected. His reference to “There’s many black ears here to listen†always struck me as foreshadowing the lyrics about racial unity later in the song, and bemoaning the fact that there is such a thing as a separation between “white†and “black†music, with a call on punks specifically to be aware of that divide and to focus on fixing it rather than “fighting for a good place under the lighting.†In 1979, with the entire punk movement only three years old, Strummer calls out those in the movement who have already sold out to corporate interests, and if you replace his lyric about “Burton suits†with “Hot Topic shirts,†his claim that corporations were “turning rebellion into money†still rings eerily true today.

By all accounts, both the UK and US versions of The Clash are near perfect albums, and both are absolute punk classics. But, even though it was rearranged and chopped up by a record label, I think the US version came out a little stronger, a little harder, and a little smarter than the UK version. The Clash was a great band from day one, but they improved with age, and the US version shows a little bit more of the maturity that they developed in the two years after their debut album’s release.

[1] Gilbert, Pat. Passion Is a Fashion: The Real Story of the Clash. London: Aurum, 2009. Print. 395-396

[2] The Clash: Westway to the World. Dir. Don Letts. Perf. Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, Topper Headon. 3DD Entertainment, 2000. DVD.

[3] Gilbert 385-387

[4] Gibson 254

[5] Gilbert 187