Much ado has been made about Dale Crover’s drumming. The fact is, most people seem to think he’s one of the greatest drummers in rock and if you check out Bullhead or The Bride Screamed Murder you’ll see that it’s the truth. But, Crover isn’t awarded his medals because he’s extremely complex or because he’s a technical wizard- rather, Crover is given is props because he’s the opposite of that. Yes, he is a boom-bapper, smashing down those drums with the power of Keith Moon, giving the Melvins the raw power that drives them forward. But whereas many skilled skinsman would focus on “drumming,” Crover seems to focus on the song itself, driving a tune forward when needed, supplying the perhaps invisible force, all while adding tasteful accents when necessary... and leaving space when space says more than volume. Mick Jagger is a man of few compliments but there’s a reason why he somewhat uncharacteristically always compliments Charlie Watts’ drumming. That reason is, Charlie Watts knows when to fill up the room and when to get out, and, he’s so good at it you don’t even realize he’s doing it.

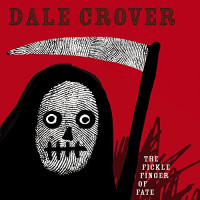

And so Crover, on his debut album The Fickle Finger of Fate takes to the same approach. The songs here are basically rooted in Melvin-ish rock/metal with rumbling guitars, pounding drums, and askew lyrics. But, whereas the temptation may be for Crover to make the album a drumming demonstration, he wisely builds the album around songs and not the drums. “Bad Move” operates in a hazy melt, with Crover drifting across the speaker like something unwholesome while Steven McDonald’s doomy bass plays off Crover simple, hard striking. The result is a tune that is as spooky as it amorphous. That is to say, the song is intriguing because while it does give Crover’s drumming skills focus, it more a showcase of his construction skills.

Likewise, “Little Brother” may give slight winks to Crover’s influences. The first half has a sunny drifting accentuated by an acoustic guitar that reminded me of the more expansive parts of Tommy. Meanwhile, near the end, the end sounds like it has ringing open chords ala that famous Keith Richards style. All of these influences made their names because they were composers first and players second, and Crover does the same.

The album is tied together with short, distorted drumming interludes which originally appeared on a hyper-limited lathe. Perhaps wanting to elevate the status of the “Drummer’s solo” album, Crover, instead of running through routines, twsits and melts his drums sound so they sound synthetic and fried. He seems to want to show the texture that can be created by rhythm, rather than his own particular chops. Not to get too existential, but Crover seems to be saying “worship the drums and its capabilities” rather than “worship me and my capabilities.”

And that’s really the trick, here. Solo albums are usually exercises in ego puffing. Crover doesn’t seem as interested in declaring his own awesomeness as he is is exploring both his instrument and song construction, playing equally with avant-garde and classic set ups. It’s a testament to the man’s skill and creativity that despite being the main piledriver for the Melvins for over 33 years, he’s able to find new galaxies between snare and cymbal.