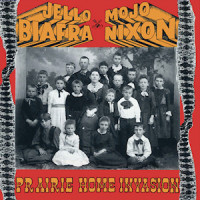

When you’re a fifteen year old punk rock kid, who worships at the thrones of Ian Mackaye, Jello Biafra, and various other names from the punk rock starter kit you tend to buy anything with one of their names on it. So, when I saw Prairie Home Invasion in my local record store, of course I bought it. At the time, aside from a reference on a Dead Milkmen album, I’d never heard of Mojo Nixon. Nor was I familiar with most of the artists being covered or paid tribute to, save for Phil Ochs.

The album opens with a nine minute romp called “Buy My Snake Oil” wherein Jello rails against corporate rock, taking on everything from emo, alternative rock, seventies rock hold overs, and especially longtime Mojo Nixon target Don Henley. While this wasn’t a new era topically for Jello, he’d done it on the Dead Kennedys’ song “Pull My Strings” this is likely my favorite. Mojo’s band, The Toadliquors, provide great backing music throughout this album. This track proves to be one of the highlights. This is due, largely, to the phenomenal piano (though it may be pronounced pianee given the style) of Pete Gordon, who provides great instrumental interludes throughout the song.

Elsewhere on the album, you’ll find the Jello and Mojo teaming up to rework a number of great songs that take on such topics as deforestation, atomic power, truckers, and the divine drinking abilities of Jesus Christ. While all of these are great takes oo great songs and Jello and Mojo are able to bring a bit of their sardonic whit to the songs, they don’t stand up to the slightly more original material content on the album. Their modernization of Phil Ochs’ classic “Love Me I’m a Liberal” trades the political views of fair weather liberals in the 1960’s for those of the early 1990’s. Interestingly, many of the issues they’re touching on, hadn’t changed simply the contemporary examples that existed of them.

One of the best fully original songs on the album, is “Nostalgia for an Age that Never Existed” as Jello Biafra takes aim at an over romanticized version of the 1950’s, the hypocrisy of baby boomers when it came to raising their own children, and finally pointing the finger back at the genre that birthed him, punk rock. The song points out one of the central reasons Jello Biafra can remain relevant while also pointing to one of the central ironies of many of those who worship at the throne of Jello. His ability to change, adjust, and work within any number of styles of music has kept him from fading into irrelevancy or became a parody of himself by trotting the same tired act out on stage thirty years after the last studio album was released. The central irony of this, and him advocating for punk culture needing to be able to evolve, is many of his deepest devotees are always quick to remind everyone what is and is not punk.

Of the songs where Mojo Nixon takes over lead vocals, “Let’s Go Burn Ole Nashville Down” is the most successful. It takes aim at the pop songs and stars that spent much of the eighties and nineties masquerading as country music. In addition to pointing a finger at country musicians who have images more manufactured than the plastic their music was released on, the song doesn’t forget someone was pulling the strings as well. It is quick to point out that Jimmy Bowen, while being behind some great records, spent a lot of time cleansing country music and taking it back to something much more akin to what the genre resembled prior to the rise of outlaw country.

While the album is certainly highly entertaining, and is well played it doesn’t have much in the way of staying power. That is to say, when people look back at albums that were as indebted to country as they were alternative rock in the early nineties … this isn’t a release people are going to be bringing up. As good as it is, this album doesn’t compare to the best work by bands like Uncle Tupelo, The Bottle Rockets, or even the albums the Drive-By Truckers would be releasing just a few short years later. In short, it’s definitely not just for people looking to round out a collection, but I’d venture to guess this isn’t the album that made anyone decide they were going to make music for a living.