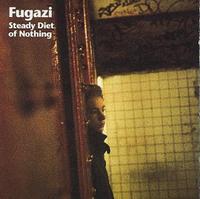

There has never been another band in existence quite like Fugazi. Punk was their ideological cornerstone, but their flexing of genre, musicality, and style made them difficult to quantify cleanly. They revolutionized post-hardcore with pioneering jams like “Margin Walker” and “Waiting Room” while also fearlessly drawing influence from art rock and funk, daring to experiment with tempo, rhythm, and vocal technique throughout the group’s storied career. The history of Fugazi was dotted with lauded highs and more stagnant patches, but with every release another unique facet of the band was exhumed; 1991’s Steady Diet of Nothing attested to that idiosyncrasy.

Fugazi boldly referenced social, political, and human topics in their music, with lyrics and song titles that were purposefully explicit without ever coming across as heavy-handed. Steady Diet of Nothing, the band’s second full-length, fittingly cites Bill Hicks, an American stand-up whose dark comedy was steeped in anti-establishment sensibilities and controversial satire. The record was born in early ‘90s Washington, D.C. during the aftermath of the First Gulf War, an epoch charged by public criticisms of the media, government, and militarization, and Steady Diet embraced these topics. Exemplary tracks included but were not limited to “Dear Justice Letter” and “KYEO”, a lamentation over Justice William J. Brennan Jr.’s retirement and a hawkish call for constant vigilance, respectively.

Guy Picciotto and Ian MacKaye comprised the well-oiled machine behind Fugazi’s vocals and guitar, a combination of exuberance and grit akin to artists like Jawbox or Big Black. They sang laconic lyrics in their own individual styles, suiting them to the tonal or framing needs of each song and providing backing vocals for added emphasis or call-and-response. For instance, MacKaye’s gravelly timbre on the bodily integrity anthem “Reclamation” punches out the titular word repeatedly in the chorus, while Picciotto’s confident flamboyance emulated the darkly humorous guise of the catchy “Nice New Outfit”. Picciotto and MacKaye took turns commanding the microphone track-for-track throughout Steady Diet of Nothing, which evenly showcased the duo’s vocal range and essence.

“Exit Only” opened the record with the punk equivalent of an orchestra tuning their instruments. Brendan Canty and Joe Lally, drums and bass, flipped the script and used the introductory guitar feedback as a foundation, bringing their creative interplay to the fore with a crisp snare and brooding bassline, interspersed with the sudden choking bursts of silence that had already become a staple of the Fugazi sound. Their rhythmic contributions and counterpoint on “Long Division”, a somber, ballad-esque beauty, haunted the listener by lingering in the subconscious long after the tune had ended. Canty and Lally treated the slower, some might have said banal, songs on the sophomore album as a blank canvas for them to forge rhythmic sequences and grooves that inventively superseded the orthodoxy of late 80s punk and hardcore.

Infused directly at the midpoint of the record was title track “Steady Diet”, a noisy extemporization that consisted of whirling distortion, a baleful bassline, and evocative drumming. The instrumental intermission was surprising but calculated; it offered an opportunity for Fugazi to brandish their unconventional musicianship on their own terms, unshackled from vocals. “Stacks” and “Latin Roots” were other strong illustrations of this diversity, musically innocuous on the surface with a subterranean eccentricity. Striking lines like “America is just a word, but I use it” and “It’s time to meet your makers” were conveyed huskily over deceptively complex arrangements and bright 90s tones, an unexpected but triumphant juxtaposition of sounds.

Steady Diet of Nothing confirmed that rejection of mainstream conventions was at the heart of the band’s musical philosophy, even in its nascent form. They exercised the Stravinskian notion that every instrument had a distinct voice and purpose while simultaneously challenging embedded ideas of what those purposes were, which united them together on an equal performative plane. A major theme of Fugazi records was their abdication of guitar’s supreme reign; though Picciotto and MacKaye executed distortion, harmonics, and other imaginative devices effectively, the bass and percussion parts were more defining of the band’s identity. They hammered their messages home with emphatic repetition and throaty delivery, bypassing the need for the aggression of extremes and instead trailblazing the punk landscape with anomalous ingenuity.