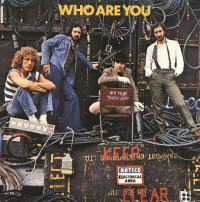

Since forming in 1964, The Who were a band that had always rested more or less evenly on its four founding members. Pete Townshend wrote off-beat but catchy songs, combining introspection with theatrical bombast, and then handed them off to Roger Daltrey, a strutting, mic-swinging showman, to croon and howl. Sonically the songs were set apart by the technically brilliance of John Entwistle’s bass playing and the somewhat less technical, but no less brilliant, percussive fireworks of Keith Moon, The Who’s drumming savant. Unfortunately, by 1978’s Who Are You, some of those foundations were beginning to crumble. Always a hard partying band, leaving a trail of trashed hotel rooms in their wake, the drinking and drug use was beginning to catch up with them, Moon in particular. During the recording of Who Are You his drinking had eroded his talent to the point that Townshend threatened to kick him out of the band. Moon cleaned up and buckled down but to some extent, the damage was done. The drums on the album lacked the ferocity of earlier efforts and in the case of “Music Must Change” the drums were removed almost entirely from the track due to Moon’s inability to play. The album cover famously featured Moon sitting backwards in a chair marked ‘DO NOT TAKE AWAY’ so that his distended stomach was covered. He would die within a month of the album’s release.

Townshend, for his part, was grappling with his own drinking problems as well as questions about his place as a songwriter. The title track of the album recalled the events of a night spent drinking with a couple of non-vicious, non-rotten members of the Sex Pistols. Falling down drunk and accosted by a police officer who was also a fan, Townshend questioned everyone involved. “Who are they?” “Who is he?” A certain uneasiness with the band’s success and the adoration of their fans pervaded many tracks on the album. Its opener, the creatively named “New Song”, served almost as a confessional for a songwriter who has begun to feel his fingernails hit wood at the bottom of the barrel: “I write the same old song with a few new lines/And everybody wants to cheer it/I write the same old song you heard a good few times/Admit you really want to hear it”. Townshend’s frustration with his songwriting struggles seemed to be mirrored by a frustration with his audience’s failure to either hold him accountable or embrace a new direction along with him.

The spectre of that new direction loomed large over the entire album. Since 1971, Townshend had been trying to write Lifehouse, a rock opera to follow up on the success the band had with 1969’s Tommy. Lifehouse had a steel kite’s willingness to get off the ground and Townshend had been cannibalizing it for songs almost since its inception, the most notable of which being “Baba O’Riley” on Who’s Next. By 1978, Townshend was still writing songs with an eye towards including them in Lifehouse, with its increasingly nebulous plot centered around a dystopian-future, music-as-religion cult and its harmonic, pseudo-rapture at an illegal discoteque. Unfortunately, the songs Townshend was writing that appeared on Who Are You were a little more “1921” than “Pinball Wizard”. Who Are You was populated heavily with songs loaded with exposition for a story they weren’t getting a chance to tell. Even Entwistle’s writing seemed to feel the gravitational pull exerted by his main songwriter. He had three compositions on the album, the best of which, “905”, feels a bit like Crosby, Stills and Nash wrote a song for the “2001: A Space Odyssey” soundtrack.

Musically, however, Entwistle fully supported his end of the bargain. Who Are You was filled with his trademark rumbling bass-solos-as-main-riffs. Sitting high in the mix and running up and down his range, his was the strongest instrumental offering on Who Are You and fully on par with previous albums. Daltrey seemed to suffer from the music moving away from the scream-filled ‘Maximum R&B’ of the band’s early days to the rock and roll recitative demanded by their new rock opera-focused direction. He sang the words ably but lacked the jaw-jutting conviction of his earlier days and had less chance to flex his full dynamic range, singing most of the words at the higher end of his register. Rather than siding with the emerging punk movement, whose aggressive power chords he had heavily influenced, Townshend’s compositions tacked aggressively the opposite way. “Sister Disco”, perhaps the second strongest song on the album which seemed to be unsure if it was mourning the lost youth of disco or dancing around its funeral pyre, took its name from the reviled genre that, along with prog rock, seemed to have some control over Townshend. Almost every track on Who Are You was filled with layer after layer of intricate keyboard and synthesizer lines. What had been a deft hand on earlier productions was now heavy, adding horns and orchestration which introduced their own wrinkles and tensions into recording (Daltrey would knock famed producer Glyn Johns unconscious in a fight over a string arrangement). While technically impressive, the overwhelming production crowded out the core of the band musically, with Townshend’s trademark guitar strums pushed out of the spotlight.

With Moon gone, The Who were essentially finished. Although they would release two more studio albums in their original run, Who Are You was for all intents and purposes their swan song. A band who had ridden in on the British Invasion and managed to stay a juggernaut through the summer of love and into the era of arena rock and punk, they went out fighting, self aware and pushing themselves to find new directions. As much as Townshend derided himself for writing the “same old songs”, in some ways the great failing of Who Are You was that it lost itself trying to get somewhere else. Perhaps with a surviving Keith Moon, the band would have distilled that new sound and reduced Who Are You to a footnote, a stop along the way. Or would they have followed others of their generation, turning quickly into the greatest-hits-rehashing, classic rock dinosaurs they have since become? As it is, Who Are You is the last thing the four would play on, and it will have to do: a deeply flawed but honest memorial.