One of the main reasons that Morrissey has sustained over the decades is that he refuses to be what the public wants him to be. Whereas many of his most hardcore fans would prefer that he just crank out lovelorn sad-jams like “Everyday is like Sunday” and “Suedehead,” he then turns around and writes songs about how much he hates cops (“ganglord”) or how much he loves it when matadors get their intestines torn out (“the bullfighter dies.”) Whereas many other artists would give the fans what they want, thereby sinking into insignificance with each successive release, Morrissey has wrestled against the perceived definition of himself and has kept people guessing as to who he actually is. It worked for Dylan. It worked for Bowie. It worked for Morrissey.

Well, it worked for Morrissey until the past five years or so. Nearly every article about Morrissey for the past few years has included a sidebar on his recent… controversial… statements or actions. The most recent one was where he wore a pin from the organization “For Britain” which kinda sorta maybe seems to be a pretty racist organization. Morrissey has alluded to the fact that he wore the pin because they support animal rights, but in true Moz style, he has been frustratingly vague as to many specifics regarding what he actually does believe in.

And in fact, this stance has harmed his public perception to a fair amount. Even many of his most diehard fans have turned on him, with others hoping for the best. Now, it might not be fair to mention an artist’s entire history and it might not be fair to recite their flaws in a review of the art, but on his newest album, I am not a dog on a chain Morrissey directly addresses this issue.

A defiant tune in a string of Moz-defiant-tunes, Morrissey directly declares that he doesn’t really care what people think of him and he won’t bow to what the media wants him to bow to. It’s a bold statement in this case, to be sure. And it is somewhat refreshing that Morrissey says he’s going to stick to his guns even if it costs him fame and money. Many other popular punk bands certainly have censored themselves or relaxed their convictions in the name of bucks. Still, it would be a little easier to chew on this if Morrissey would clarify what his stance actually is as opposed to what his stance isn't.

Yet, as before, Morrissey still wears a cloak of tactical-vagueness. He says he doesn’t believe the media on the title track- but is this from the stance in the vein of Crass telling you to distrust Rupert Murdoch style politics or is it in the vein of Trump not-so-subtly suggesting that he’s the only guy you can trust? Morrissey doesn’t tell us, leaving him as much a puzzle as he was before. Whether or not you are comfortable to work through a puzzle that may end up being dangerous is up to you.

But then, whereas it seems the album will be the Morrissey manifesto wherein he throws off the shackles of what people want, he then, again, pivots. Despite the chest beating title track, confoundingly, the remainder of the album is the exact kind of thing Morrissey fans want.

Throughout both sides, he waxes tales of heartbreak, insecurity, and youthful counterculture, usually in the form of a third-person narrator. Opening track “Jim Jim Falls” Morrissey locks his two favorite topics together – love and suicide. It’s not clear if he’s equating the two or writing about the two simultaneously, but in true Moz style, the merger is delivered with unflinching genuineness. This might come off as melodramatic in weaker hands, but because Mozzer has swum in the waters before, he’s able to make it abstract and convincing. This track, and others on the album, show producer Joe Chiccarelli using his trademark mega-production. Every note is delivered with crystal clear clarity and every drum beat sounds massive. Also in true Chiccarelli style, there’s a fair amount of experimentation hidden behind more standard rock arrangements. “Jim Jim Falls” is built off a buzzing, electric beat. “Love is on the way out,” which finds Morrissey smacking down on trophy hunters and love itself in equal measure, has studio-sirens howling in the background between passages to the point where the song almost feels like a daring remix of itself. Again, perhaps surprisingly, it works.

That’s in part because Morrissey sounds as rich as he ever has. The man is famous for his voice and throughout the album, he puts that velvet croon to use. There’s a certain confidence here, too. Almost since the beginning of the Smiths, Morrissey has been both saluted and chided for his unique delivery style and lyrical content. As Elvis Costello once said: "Morrissey writes wonderful song titles, but sadly he often forgets to write the song."

I don’t agree with that attack, mind you, particularly here, whereas, as stated above, Morrissey is giving the fans what they want- yet, in lieu of imitating himself, his expanding upon his legacy. “The Truth About Ruth” finds Morrissey attacking transphobia and in trademark style, he ends the track with a withering statement of the human condition: “sooner or later, we are all cut down.”

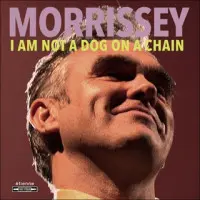

No doubt, with his recent actions and comments, and especially with his frustrating vagueness about certain topics, Morrissey is challenging his own fans as much as his detractors. That’s especially true with I am not a dog on a chain whereas Morrissey delivers his most Moz-like album since Years of Refusal (and maybe even Vauxhall and I). But maybe that’s the point. Just as Morrissey claims he isn’t affected by global media and that he makes up his own mind on the title track, he’s urging his fans to work out who Moz really is for themselves. At this point, I’m not sure myself. Though, it may be a clue to Moz’s mindset that the album cover itself is focused to such an close-up that, while the picture looks normal from a few yards away, if you hold it up for yourself, you can see that Morrissey’s face is heavily distorted by the camera lens and angle of the shot.