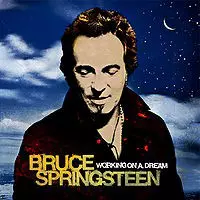

Ladies and gentleman, the Second Coming of Bruce Springsteen is about to end. Beginning with 2002's The Rising, the Boss has had an excellent comeback run of political albums during the George W. Bush administration. The Rising helped heal America's wounds post-9/11, while Devils & Dust, We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions and Magic took the country's government to task for its war profiteering abroad and ignorance towards mounting domestic issues. But with Bush out and Barack Obama in, Springsteen struggles to find relevance, or at least a solid collection of pop songs, on Working on a Dream, his 16th studio album. It's by no means a bad album, but it is middling and uneven, much like Tunnel of Love, the last decent record Springsteen released before his '90s creative dry spell.

The record tiresomely opens with "Outlaw Pete," an eight-minute Western epic that's aesthetically on par with Bob Dylan's "Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts," just with way more overblown orchestral flourishes. That's not the first song comparison that will come to listeners' minds, though. Magic producer Brendan O'Brien returns to again bury Bruce's simple songs in Phil Spector-ish layers of strings and backup vocals, so I'm not sure who to blame for the background melody on "Outlaw Pete." All I do know is that it cops a feel off of the first half of the melody to Kiss' "I Was Made for Lovin' You." It's a minor detail -- five notes -- but it's the sort of sudden jolt that derails the whole tune. Like a friend who uncharacteristically drops a racial slur, those five notes become more and more bizarre and grating with every listen (and give a little more credence to the accusation that Springsteen ripped off Tommy Tutone's "867-5309/Jenny" for "Radio Nowhere"). Now, the song is already in a bad way for its nearly comical Western theme. I can't comprehend why "Outlaw Pete" would bite "I Was Made for Lovin' You" when it's (A) fairly well-known, (B) not particularly well-liked, and (C) freaking disco-metal. The song's running length adds a third reason to press "skip" right after "play."

Track two, "My Lucky Day," makes "Outlaw Pete" seem like a misstep. It's half as long and twice as catchy. The lyrics have a gambling theme going, but they're vague enough that the tune could be about anything -- a good night at Atlantic City or a love song to Barry Obama. Really, it's not important to feel the words on this one too much. The beat is quick, the guitars are rocking and Clarence Clemons swoops in with his trademark sax to ensure that "My Lucky Day" stands out as one of the best tracks on the record. Then "Working on a Dream" starts.

"Working on a Dream" has got to be the most lazily assembled Springsteen song ever. The guy used to cram his songs with description and frenetic rhyme schemes; here, he settles for repeating the song's title for like two-thirds of its running time. That dream must really take some workin'. "Working on a Dream" is the second clunker on the album. "Queen of the Supermarket" adds a third thanks to tepid production, a stupid story and the lamest use of "fuck" since The Ghost of Tom Joad's "My Best Was Never Good Enough." Profanity can emphasize emotions, but with Bruce it just feels like a crutch.

"What Love Can Do" evens the keel out, at least musically. The lyrics repeat the sex/religion duality used on Magic's "I'll Work for Your Love" to less effect. It's a watered down repeat, but it beats "Queen of the Supermarket." After that, the record enters a mid-album malaise. O'Brien's production ensures that the songs at least sound like Magic's slick rock, but again, the melodies and words just aren't quite there. O'Brien pulls back slightly on "Tomorrow Never Knows," a subtle country track that would've fit in fine on the similarly stripped Devils & Dust. Love song "Life Itself" begins the record's ascent back up. Bruce's vocal take is restrained compared to the bravado of "Outlaw Pete"; it's a refreshing moment of tranquility. Working on a Dream often struggles to find the Big Rock Statements© that came so easily on The Rising. But when Springsteen settles into pretty-sounding quiet songs like "Life Itself," he can actually be quite moving.

The somber double dose of "The Last Carnival," a sequel to "Wild Billy's Circus Story" from The Wild, The Innocent, And the E Street Shuffle, and "The Wrestler," an ode to Mickey Rourke's stripper-loving, heart attack-having character Randy the Ram from the acclaimed film of the same name, close out the record. These later tracks' humility and better lyrics redeem Working on a Dream slightly, recalling the similarly somber Tunnel of Love. In a lot of ways, Working on a Dream and Tunnel of Love feel connected. Both work best at their quietest. Both follow uneven yet hugely successful rock records (Magic / Born in the U.S.A.). Both caught the artist in the middle of switching gears (hating Bush / hating Ronald Reagan). And both marked an end to Springsteen's creative cycles (2009/1987, although I do want to state for the record that 1995's The Ghost of Tom Joad wasn't too bad). Unlike Working on a Dream, though, Tunnel of Love had the good sense not to rip off Kiss.