This year marks the 25th anniversary of AFI’s seminal album Black Sails in the Sunset. The album was released in 1999 and was their first output to feature their current lineup. The band are currently supporting 30 Seconds to Mars during their summer tour. Toronto-based journalist Graham Isador reflects on AFI’s influence on the punk scene and conducting interviews with the band for over 20 years. Read his article below!

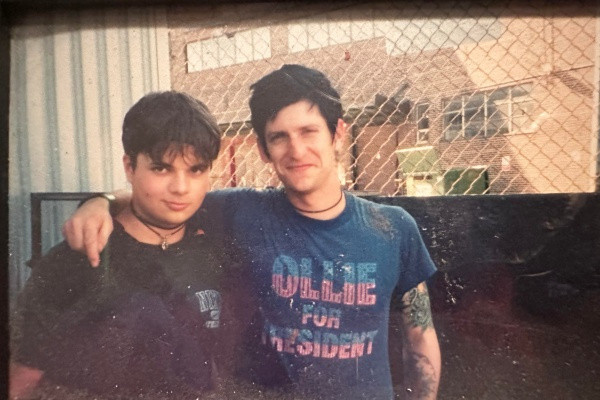

Graham Isador and Adam Carson of AFI 2003

Graham Isador and Adam Carson of AFI 2003

The first time I interviewed AFI I was fourteen years old. Getting the interview was sort of a fluke. It was my freshman year of high school. I didn’t have a lot of friends and tried to hide that fact by going to a lot of concerts. A burdensome accessory to my older brother, dragged along to church basements and legion hall gigs all across Southern Ontario. When I wasn’t at a show, I was on a message board. Arguing over now antiquated topics like the concept of selling out. What is and isn’t punk. Those forums were formative to my adolescence. I fell in love for the first time, running headfirst into teen romance with a beautiful goth girl I’d never actually meet in person. I was introduced to an incredible array of literature and film. Books by Noam Chomsky and high art movies like The Fifth Element. But the thing that left the most lasting impression was learning about zines.

Across the message boards, dozens of zines and music blogs popped up every day. They offered poorly researched essays about the war in Iraq. How-to guides on buying girl jeans as a man. Xeroxed pages sent through snail mail burst with scathing album reviews and conversations with bands both big and small. And a lot of these zines wanted contributors.

Writing about music felt like a chance to actively participate in a scene that I’d only been observing. Sheepishly I submitted some samples, actively trying to hide my age, fully unaware that the people running the websites were at best a year or two my senior. To my surprise they agreed to publish my work. Just like that, I’d have an audience of dozens.

AFI were my favorite band. They were on the cusp of releasing an album called Sing the Sorrow. Hoping to speak with the group, I emailed the webmaster of their forum — a name listed at the bottom of a geocities page — offering a feature interview in a publication called THE LOST SOULS. Three weeks later and a little bit of luck, I was standing in front of the band almost paralyzed with excitement. Forgetting my questions I spent the majority of the time gushing about how their music saved my life. How AFI were the future of punk. For their part, the group was very polite.

What I didn’t know at the time was that I’d continue to have conversations with AFI over the next 21 years, chronicling their work as a professional journalist in places like VICE and GQ. That and the thing about the band being the future of punk was more or less spot on.

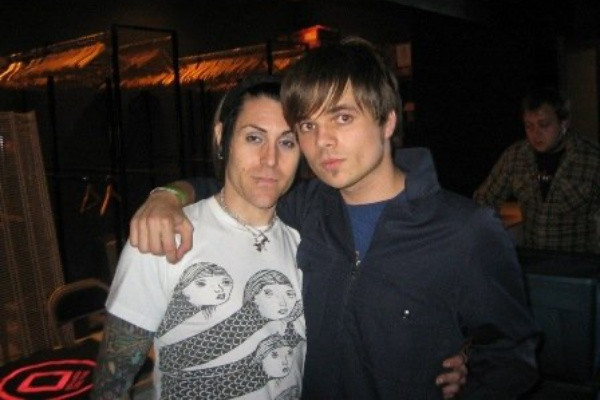

Graham Isador and Davey Havok of AFI 2005

Graham Isador and Davey Havok of AFI 2005

During the intro to that initial interview I tried to describe what I loved about AFI. The band replaced the camp elements of horror punk with a bit of romanticism. If the Misfit’s crooned about wanting your skull in a joking cadence, AFI yearned for it. Spooky imagery of vampires and graveyards were played with the utmost sincerity over the backdrop of melodic hardcore and hints of post-punk.

The band’s aesthetic drew heavily from legends like Siouxsie Sioux and Peter Murphy, incorporating aspects of fetish scenes and askewing gender roles. While the influences were obvious if you knew how to look for them, AFI’s sound and presentation felt entirely new during the late nineties and early aughts. In the punk scene it echoed like a revelation. The three album run of Black Sails in the Sunset, The Art of Drowning, and Sing the Sorrow spawned hundreds of imitators.

Over the next decade watered down versions of the band’s sound and fashion became the de facto uniform for the modern emo movement. It’s a label -- along with the term goth punk -- that AFI have actively rejected. Understandably so. While many “emo” bands became massive arena acts, the genre comes with a lot of baggage. Lightweight pop songs about broken hearts and poorly applied eyeliner with little regard for the sources it draws from, never quite capturing the depth that AFI brought to the work.

The band’s impact on the scene would be undeniable. While they’d go on to write platinum selling albums and spawn massive radio hits, many of copy-cat acts eclipsed their popularity. During my most recent interview with the group -- who were very kind enough to pretend to remember our many chats over the years -- I asked about that uneasy legacy, suggesting that some bands had gotten the answers by cheating on the homework. Frontman Davey Havok and guitarist Jade Puget were diplomatic with their response.

“I don’t entirely disagree. I did encounter many people at the time who were dressing in a certain way or presenting themselves similar to [our look]. But it didn’t seem to come from a similar background or have similar attention to detail,” said Havok. "Musically speaking I don’t know if they had the same musical inspirations.”

“I mean some of it was kind of obvious and that's fine,” said guitarist Jade Puget. “That's great. It's flattering. It was never like…whoa. Look at this guy. This band is copying what I was doing 10 years ago. We all take from the people that came before us, and we do our own version of it. And that's just the nature of art and creativity in all forms.”

Not wanting to push the issue, I got a bit sentimental instead. Talking about how the band’s expression opened up the doors for myself and a lot of fans to come into their own. Their art was permission to express and embrace some of the darker elements and feelings bombarding a certain type of listener. Even within the context of the punk scene, it felt like an oasis. Broadening that out a bit, I think the trickle down effect from the band playing with gender roles and societal norms helped a lot of people. Saying the words I felt a bit surprised. The adult version of what I’d expressed all those years ago. Again, the band was very polite though not entirely willing to take what I’d ascribed to them.”

“The good news is, is that someone somewhere, has influenced people to present themselves in a way that they feel comfortable, regardless of social norm, regardless, regardless of religious oppression -- which is really what we're dealing with in most issues that affect society -- and people just fucking ignore that,” said Havok. “Regardless of where it came from, it’s wonderfully positive. I love to see it.”

-- This year AFI celebrates 25 years of their album Black Sails in the Sunset. It was my first AFI record. To celebrate the anniversary, I’ve been spending a lot more time with the tracks. While the band has certainly grown past that on an artistic level, there is an urgency and rawness that’s hard to overlook. Looking back now, it’s easy to see how the record set them on the path they're on, but hindsight is always like that. Instead, I’ve been trying to place myself in the mindset of when I first heard the record. When everything seemed new and full of possibility.